Introduction

The core theoretical model is known as the core self model. It is an integrative person-centred model which was especially developed for this course. It is fundamentally person-centred in that it draws heavily on the work of Carl Rogers and other person-centred writers, and shares with its humanistic counterpart many of the philosophical assumptions and theoretical hypotheses that shape person-centred theory and practice. It is also person-centred in that it rests firmly on the belief that ‘the relationship is the therapy’ (Mearns & Thorne 2000) – in other words, that it is the quality of the relationship between counsellor and client that lies at the heart of the effectiveness of the counselling process.

It is, however, also an integrative model. Firstly, it is integrative in that it seeks to draw together the person-centred and the spiritual in a meaningful synthesis. It rests firmly on the assumption that all human beings are spiritual beings, and that the spiritual dimension of human nature and experience is a fundamental part of what it means to be human. It sees human beings are complex living unities of body, mind, soul and spirit in whom the various aspects of being and experiencing are closely interwoven and hence recognises the importance of being willing and able to address this dimension of human experience in the counselling room.

It is also integrative in the sense that it seeks to draw together relevant insights from psychology, counselling theory and philosophy, and from Christianity and the world’s other major religious traditions.

The Core Self Model Framework

The following summarises the core assumptions of the core self model:

1. THE PHILOSOPHICAL FRAMEWORK

CORE ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT HUMAN NATURE

1. That spirituality is a universal human experience

This core assumption rests on the belief that all of us have a spiritual as well as a psychological dimension to our being, that all of us are spiritual beings whether or not our spirituality finds its home within a particular religious faith. Our spirituality is, as Elkins (1998) describes it, ‘an inborn natural potential’. All of us are body, mind, soul and spirit.

2. That the essence of our human nature is spiritual

The spiritual dimension of our being is the deepest, most fundamental part of our human nature. We are first and foremost spiritual beings and our spirituality is the core of our being. As de Chardin (1955) puts it, ‘We are not human beings having a spiritual experience; we are spiritual beings having a human experience.’

3. That all of us have intrinsic value, worth and dignity as human beings

This assumption echoes the affirmation of human worth, dignity and potential to be found not only in humanistic philosophy and psychology and in person-centred theory and practice, but also in every major world religion and spiritual tradition. It calls for an attitude of deep respect for and unconditional acceptance of each other.

4. That the core of human personality is essentially positive

The assumption here is that no matter how destructive of ourselves or others our desires, impulses or behaviour may be at times, somewhere deep within us at the heart of our human nature, the essence or core of our being – what in humanistic terminology might be called the true self or ‘organismic self’, what this model calls ‘the core self’ and what in spiritual terminology, we might call ‘the soul’ – is fundamentally positive and trustworthy.

5. That there is within all people a potential, capacity and need for growth and development (including spiritual growth) and that this potential for growth is always there throughout the lifespan

The assumption here is that human beings are always (at least potentially) in the process of growing, developing or of ‘becoming’ and that, if the conditions are right, personality development naturally moves in a positive direction towards greater maturity and wholeness.

Within all of us, there is some kind of constructive or ‘forward-moving’ force which is present and active within us at all times from birth onwards. It seeks to preserve, sustain and develop us at all levels of our being. It is an intrinsic and fundamental characteristic of our biological make-up as human beings. We are in a sense ‘biologically programmed’ not only for survival, but also for continuous growth and maturation. It is not something we consciously choose; nor do we need to be aware of it for it to be operating within us. In humanistic psychology, this force is called ‘the actualising tendency’. Using spiritual terminology, we might call it the human spirit.

This model also assumes that this ‘actualising tendency’ drives us beyond self-actualisation (becoming fully ourselves) towards self-transcendence (reaching beyond ourselves to the transcendent or that which lies beyond ourselves however we might conceive of it – e.g. God, the Divine, the Absolute Reality, the Higher Self)

6. That this innate capacity for growth can be inhibited, blocked or distorted as a result of external factors – that is, as a consequence of the impact on us of the woundedness or brokenness of others and of the society in which we live

This core assumption recognises the full extent of both individual and collective (or societal) brokenness and its destructive impact on ourselves, and our relationships. It acknowledges that our inner longing and capacity for growth may, often as a result of our human suffering and woundedness, be blocked, inhibited or suppressed. The human spirit – the source of our innate capacity for growth – is vulnerable to the impact of deeply painful and damaging life experiences and can be quenched, though never totally destroyed, as a result of such negative environmental influences.

7. That people are complex living unities of body, mind, soul and spirit in whom the various aspects of being and experiencing are closely interwoven

The holistic nature of this model rests on the assumption that the human body, mind, soul and spirit are closely inter-connected, that each affects and is affected by the others and that it is not possible to regard them as separate or distinct parts of our being. All aspects of our human nature – e.g. the spiritual, the emotional, the rational, the physical, the relational – are seen as closely inter-related and inter-dependent.

CORE ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT THE PROCESS OF CHANGE AND GROWTH

8. That there are many dimensions of human well-being and wholeness and that they are all closely inter-connected

This assumption recognises firstly that because we are complex living unities and there are many different aspects of our being, there are many different dimensions of human well-being and wholeness – e.g. physical, emotional, rational, relational, volitional and spiritual. Secondly, it assumes that, as the many different aspects of our being are closely inter-related, the extent to which we have moved towards wholeness in one dimension will inevitably affect our wholeness in other dimensions.

9. That people have a number of fundamental psychological and spiritual needs and that they will develop their potential to the extent that these basic needs are met

This model shares the humanistic assumption that our human growth and development is to a significant degree dependent on the extent to which our basic psychological needs are met. It assumes, as Rogers did, that human beings need to experience certain ‘psychological conditions’ if we are to be able to develop our full potential and become our true selves. It also assumes, however, that as spiritual beings, we have a number of fundamental spiritual needs, our deepest human needs, and that these also need to be met, at least to some degree, if we are to become all that we are capable of being.

The model identifies the following fundamental psychological and spiritual needs:

Psychological needs:

- our need to be loved and to love, to feel a sense of belonging, to experience closeness and intimacy (both emotional and physical) in our relationships with others

- our need for the unconditional positive regard of others and for positive self-regard (or self-esteem)

- our cognitive needs – the need to acquire knowledge and understanding of ourselves and our world and perhaps, more importantly, the need to make sense of and find meaning in our experience

- our aesthetic needs – the need to experience a degree of symmetry, order and beauty in our lives

- our need to be able to exercise autonomy – that is, to have the freedom to make our own decisions and choices, to feel at least to some degree in control of our lives

- our need to actualise or realise our full potential, to become all that we are capable of becoming

Spiritual needs:

- our need for connectedness with our innermost self or soul

- our need for self-transcendence, our longing to reach beyond ourselves as individuals, to be in relationship with the transcendent, to connect with whatever lies beyond ourselves however we conceive of it

- our need to develop a viable philosophy of life and a set of values, images and symbols that enable us to make sense of and give meaning, purpose and direction to our lives

10. That people grow and develop psychologically and spiritually when they experience a therapeutic relationship characterised by the three core conditions of unconditional acceptance, empathy and congruence

This is essentially a relational model – i.e. the relationship itself is seen as the primary facilitator of change and growth and our most important ‘tool’ as counsellors is believed to be ourselves. The assumption is that, if in the context of a therapeutic relationship, we can create the right ‘conditions for growth’, if we can effectively communicate the three core conditions first identified by Carl Rogers, then, as they experience this ‘climate of growth’ – often for the first time in their lives – people will begin to grow and develop. The quality of the relationship between counsellor and client therefore lies at the heart of the effectiveness of the counselling process.

2. THE THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

CORE ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT HOW PSYCHOLOGICAL AND SPIRITUAL PROBLEMS ORIGINATE

An important part of the process of assessment is that of re-conceptualising or making sense of the client’s problems within the theoretical framework which the counsellor has adopted. Indeed, part of what any theoretical model seeks to explain is the way in which psychological problems originate and are maintained. This model of counselling draws on some of the concepts and hypotheses that form part of the humanistic person-centred approach but develops these further in a number of ways. Its core assumptions are these:

9. That the causes of psychological and spiritual problems are rarely simple and may involve a range of factors – physiological/genetic, psychological, social, spiritual – which interact together in a complex way to give rise to specific problems

This assumption reflects the model’s holistic approach and follows on from the assumption that we are ‘complex living unities’ in whom all aspects of being and experiencing are closely inter-related. It recognises the considerable complexity of human problems and acknowledges the importance of the socio-cultural context in making sense of the problems people present.

10. That past experiences and relationships (particularly but not exclusively in early life) play a significant role in causing psychological and spiritual problems

Children have a strong need to be loved and valued unconditionally. To the degree that they experience this quality of love and acceptance in their early relationships with parents and significant others, the necessary conditions for growth are present which will enable them to grow towards wholeness, to become the real or true self they were created to be, to develop healthy self-concepts and to react with others, their environment and with the transcendent (God, the Divine, the Absolute Reality, the Higher Self etc) in positive, constructive ways.

None of us, however, experience this quality of loving all of the time during our early years, and hence all of us to some degree experience conditions which limit or block our growth to some degree. We are at least to some degree diverted from the path of becoming our true selves and develop instead what might be called ‘the survival self’ which enables us to cope with living in a less than perfect world.

Note that damaging experiences or relationships encountered later in life can also have a significant effect on the individual’s belief system. The degree of impact these later experiences are likely to have will, however, in part depend on the quality of the relationships experienced in early life. Where the individual has experienced difficult or damaging relationships in early life, the impact of later negative experiences is likely to be greater.

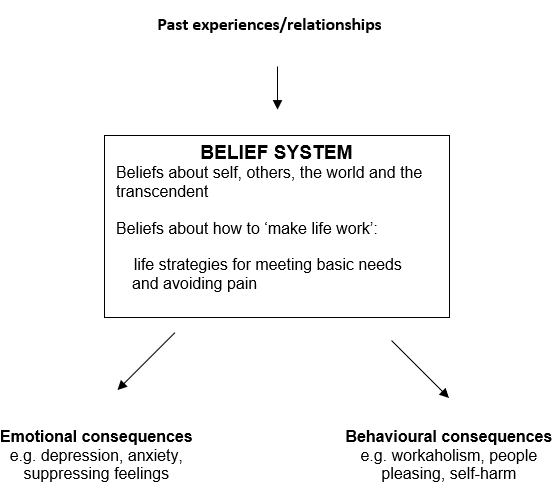

11. That, as a result of such experiences and relationships, people develop their own unique belief system (a system of beliefs and assumptions about themselves, others and the world)

The negative life experiences which we encounter, particularly in our early years (e.g. lack of reliable, mature and consistent loving, or the experience of what Clinebell describes as ‘toxic’ relationships which are characterised by neglect, rejection, or abuse etc.) help to shape our system of beliefs and perceptions and images of ourselves, our environment and others, including the transcendent. We receive ‘messages’ about ourselves, others, the transcendent and our environment from significant others in our lives, some of which we then ‘take on board’ – i.e. we internalise or unconsciously assimilate them (the word ‘unconsciously’ is used because at the time we are not aware that we have assimilated them and experience them as if they were our own). Our belief system consists both of a set of beliefs and a set of strategies.

The belief system comprises:

- beliefs about ourselves (or in other words, our self-concepts)

- beliefs about others and the world (including the transcendent)

- beliefs about how to make life work – life strategies (for meeting basic psychological and spiritual needs and for defending against emotional pain

12. That the belief systems people hold have both emotional and behavioural consequences – i.e. that people’s emotions and behaviour are to a degree shaped by (i.e. they are at least in part the consequence of) the belief systems they hold

This assumption argues that the beliefs and strategies that form our belief system to a degree shape our emotions and determine our behaviour – the way in which we interact with and relate to others, our environment and the transcendent. Our behaviour is purposeful – it is directed towards meeting our basic needs as we experience them in our private world (our ‘version of reality’ or internal frame of reference) as we perceive it. Our destructive behaviour patterns (those that inhibit our growth towards wholeness) need then to be understood in relation to our belief systems. Understanding our belief system enables us to make sense of our behaviour.

CORE ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT HOW PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS ARE MAINTAINED:

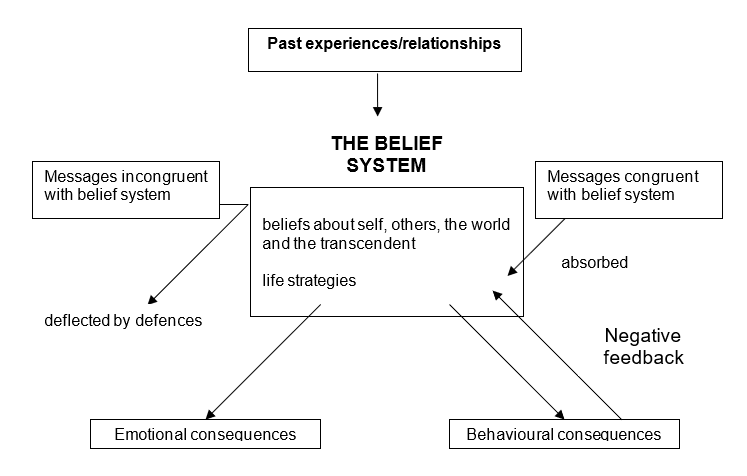

The following diagram demonstrates how the belief system is maintained:

Core assumptions:

13. That when people experience a mismatch (or incongruence) between their existing perceptions and beliefs and their actual experience, they experience anxiety which may result in the adoption of defensive strategies. These are designed to maintain the existing belief system by denying or distorting aspects of their experience.

14. That the process of changing belief systems and letting go of life strategies involves in itself the experience of a high degree of anxiety which again may result in the adoption of defensive strategies.

No matter how self-defeating or destructive of ourselves and others our belief systems are, we often cling tenaciously to them, even when we are confronted by strong evidence that they are distorted and are no longer working for us. This is because:

- they were formed during important stages of development, and usually in the context of emotional pain or trauma.

- many of our core beliefs were internalised from messages we received as children from significant, powerful others in our lives whose acceptance and valuing of us was very important to us. It is consequently very difficult for us to challenge those perceptions/beliefs/strategies particularly if we fear that we may lose the acceptance we have worked so hard to gain.

- changing our belief system means that we must work through the anxiety of facing incongruence rather than reacting defensively. The more deeply embedded and distorted the belief system is, the greater the degree of anxiety that will be experienced.

- to the degree that we have unrealistically negative self-concepts accompanied by low self-worth, we will be unlikely to have the confidence to acknowledge and face the mismatch between our perceptions and our experience, or to trust our own perceptions and beliefs rather than relying on those we have internalised.

The assumption is that as a result of our need to maintain our existing belief system, we adopt a number of defensive strategies (e.g. denial, repression, faulty thinking patterns) which are designed to protect our belief system by denying, distorting or ‘filtering’ aspects of our experience and thereby eliminating the incongruence and the consequent anxiety we experience. This process occurs at a level below conscious awareness and perception – in other words, it involves unconscious defence mechanisms. For example, if, as a result of the messages we have received about ourselves in the past, our self-concept is primarily a negative one, we will attempt to deflect any future positive messages as they do not ‘fit’ with the negative picture we have of ourselves. At the same time, those negative messages we receive which do fit with our existing belief system will be absorbed into it, therefore further reinforcing it.

15. That the belief system is maintained in part because it is perceived to be ‘working for’ the individual either in meeting psychological or spiritual needs or in avoiding emotional pain.

This assumption argues that our belief systems are maintained partly because:

- they were functional (i.e. they ‘worked for us’) at the time when they were formed, either in enabling us to some degree to meet our basic psychological or spiritual needs, or in enabling us to protect ourselves from the pain of those needs being unmet.

- they are perceived as functional now, at least to some degree, as a means of continuing to meet our basic psychological or spiritual needs and to protect ourselves.

16. That the consequences of destructive behaviour patterns often appear to reinforce the validity of existing perceptions and beliefs and therefore of existing life and self-protective strategies.

This assumption argues that sometimes, the destructive behavioural consequences of our belief system lead to our receiving further messages about ourselves or others which appear to confirm our existing beliefs and therefore serve to reinforce them. Our distorted belief systems often have behavioural consequences which are destructive either of ourselves or of our relationships with others. Furthermore, these destructive patterns of behaviour themselves have consequences which can create a kind of ‘negative feedback loop’ and thereby serve to maintain the existing belief system. For example, if an individual sees herself as boring and uninteresting to others, she is likely to adopt behaviour patterns (e.g. remaining extremely quiet and withdrawn around other people) which may result in others perceiving her as boring and uninteresting and avoiding spending time with her. The messages she receives from their avoidance of her then confirm her existing beliefs about herself (‘Other people avoid me. Therefore, I am obviously as boring and uninteresting as I thought I was.’)